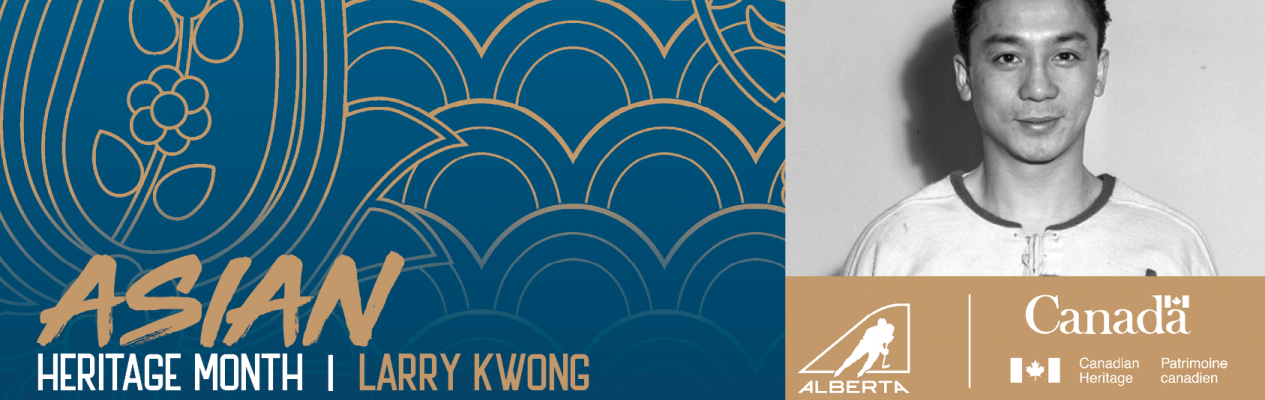

Larry Kwong’s NHL career lasted all of a New York minute, though that minute changed the game forever.

Born in Vernon, B.C. in 1923, to a Chinese-Canadian mother and a Chinese immigrant father, Kwong was one of 15 children. Kwong’s family owned and operated a grocery store, though as a Chinese-Canadian family, the household faced segregation, including being banned from voting.

During the winter months, in skates a size too big and magazines taped to his shins for pads, Kwong would spend hours on frozen ponds playing shinny with his brothers. In the evenings, they would huddle around the radio listening to Foster Hewitt call the game from Toronto and as many Canadian kids, he dreamed of one day hearing his name. Having never played organized hockey and in the days of the “Original Six,” that dream seemed a world away.

At 16, Kwong joined the Vernon Hydrophones and quickly became an offensive phenom, helping the Hydrophones to a provincial championship in 1941. Though he excelled on the ice, Kwong felt the repercussions of being a Chinese-Canadian in the 40’s, facing discrimination on and off the ice.

But his love for the game kept him pushing boundaries.

“I was afraid to tell my family, because if I did tell them that, the first thing they would say is ‘You’re not going anymore.’ And that means I couldn’t play hockey or sports. I toughed it out, just toughed it out,” Kwong said in a 2013 CBC article.

The success Kwong found with the Hydrophones did not go unnoticed as he earned himself a tryout with the Trail Smoke Eaters, a semi-professional team. Players with the Smoke Eaters received a high-paying job at the local smelter. Being Chinese, Kwong was stripped of the job at the smelter, instead spending his days working as a bellhop at a hotel.

During this time, the impact of World War II was being felt across the world and Kwong moved to Nanaimo to build war materials by day and skate with the Nanaimo Clippers by night, still dreaming of one day playing in the NHL. As the war raged overseas, Kwong set his dreams aside for his country and enlisted in the army.

Kwong’s basic training stationed him in Red Deer, where he played for the army’s Red Deer Wheelers. NHL players returning home to enlist in the military were recruited by rival teams and Kwong soon found himself facing off against men living his dream - and holding his own against them. As his comrades were sent overseas, Kwong was instructed to stay in Red Deer to play hockey to entertain the troops. And this is where he began catching the eye of professional scouts.

After the war, Kwong returned to the Smoke Eaters, where he led the team in scoring and earned another championship. In 1946, the New York Rangers extended a try-out invitation.

Topping out at five feet, six inches, Kwong’s agile speed and smooth stick handling landed him an assignment to the Ranger’s farm team, the New York Rovers. A fan favourite, his nicknames, “King Kwong” and “Chinese Clipper” echoed Madison Square Gardens during Rovers games.

Nearing the end of Kwong’s second season with the Rovers, the New York Rangers were traveling to Montreal with a line-up riddled with injuries when Kwong got the call.

“When I had the chance to become a Ranger I was really excited. I said to myself: That’s what I wanted since I was a young boy. I wanted to play in the NHL,” Kwong said in an article in the New York Times.

On March 13, 1948, Kwong dressed in his first NHL game. On that night, he became the first player of Asian heritage and the first person of colour to play in the NHL. He found a spot on the bench and that’s where he stayed until he got the nod late in the third period.

Kwong did not score, he did not get an assist, he did not get a penalty, nor did he let Montreal score. He played his first and last shift in the NHL. Kwong’s NHL career was over in a New York minute. But he opened the gate for many to follow.

Over the next five years, Kwong played in the minors, demonstrating blistering speed and unmatched goal scoring abilities. He then moved overseas to play in British and Swiss leagues before transitioning to coaching.

Despite many efforts to derail his hockey career, Kwong accomplished his goal of playing in the NHL and is an honoured member in the Alberta Hockey Hall of Fame (2016 Founder’s Award Recipient) and B.C. Hockey Hall of Fame (2013) as a pioneer of the game.

Kwong returned to Calgary where he opened a grocery store and was active in his community. He lost both of his legs due to poor circulation, yet his resilient spirit carried him to the gym into his 90’s.

Kwong passed away in 2018 at the age of 94.